Understanding that cervical spine problems can cause headache is not a new understanding, yet is still all too often overlooked. In 1956, Emil Seletz, MD… a noted Beverly Hills, CA, neurosurgeon. He was member of the esteemed faculty at the University of California, Los Angeles, medical school, and had treated more than 20,000 injury patients at the Los Angeles General Hospital. In January of 1957, Dr. Seletz published in the Journal of the International College of Surgeons an article titled (1):

Craniocerebral Injuries and the Postconcussion Syndrome

In this article, Dr. Seletz discusses post-traumatic headaches arising from whiplash injuries. He states:

“Analysis of the symptoms of several thousands of such patients will reveal that headaches persisting for months or years after a cerebral concussion are real and that they are extracranial in origin.”

He states that there are three primary extracranial sources for these post-traumatic headaches:

1) The upper cervical spinal nerve roots.

2) Elements of the trigeminal nerve.

3) A combination of the two.

In every whiplash injury, the head is involved in sudden acceleration or deceleration, causing some unnatural movement, rotation or strain of the upper cervical spinal roots and muscles.

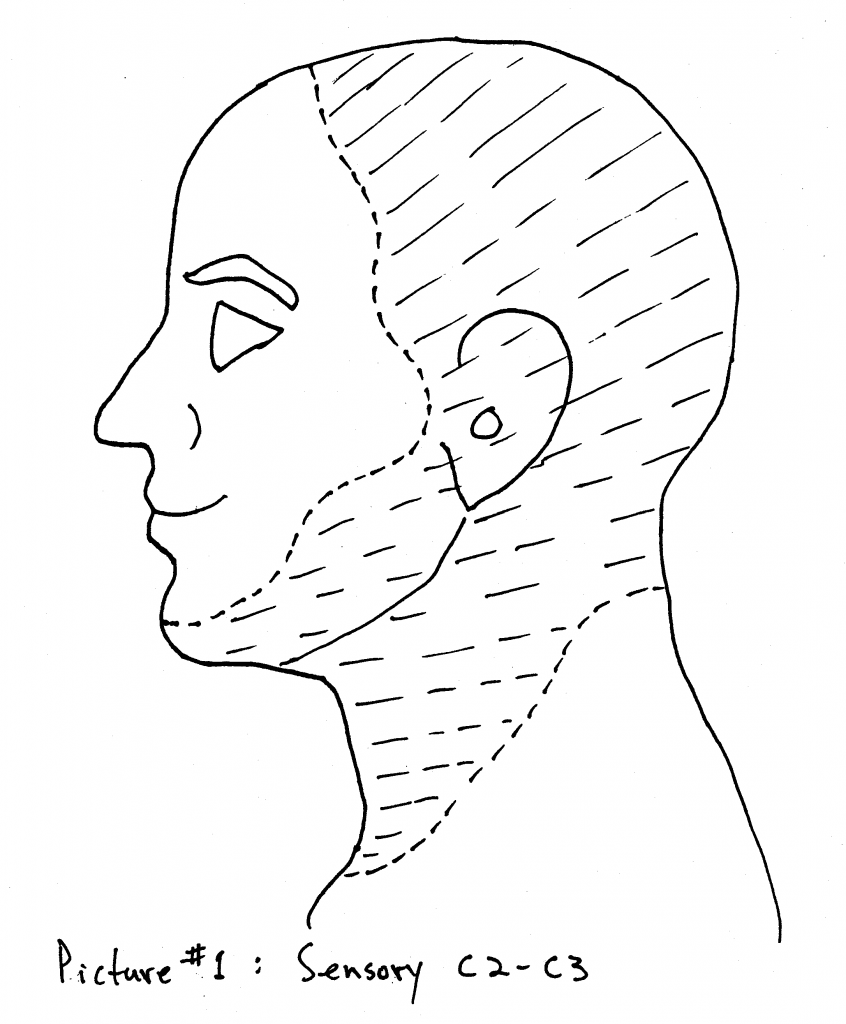

The 2nd cervical nerve root becomes the greater occipital nerve and supplies the major portion of the scalp, the upper portion of the neck and portions of the face. [PICTURE #1]

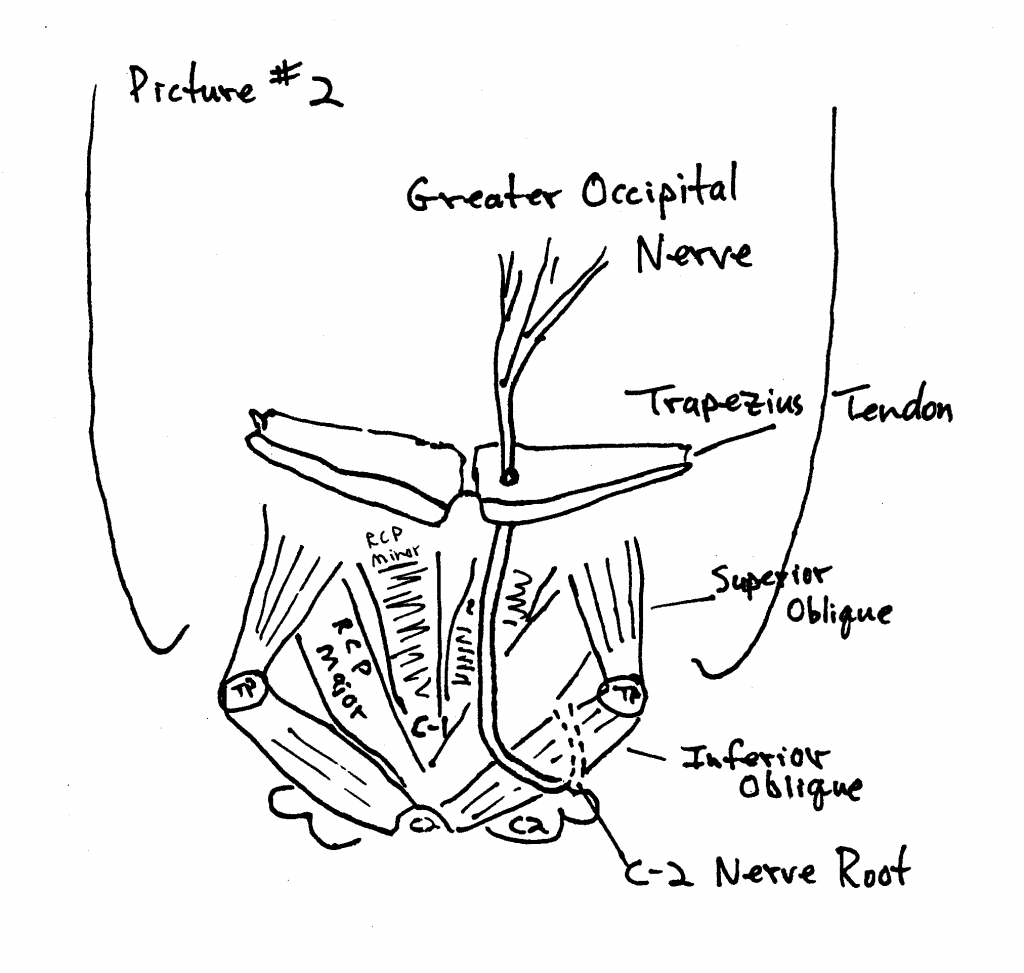

The 2nd cervical nerve root is more vulnerable to trauma than other nerve roots because it is not protected by pedicles and facets. The 2nd cervical nerve root leaves the interspace between C1-C2, courses down and winds under the inferior oblique muscle, then proceeds upward as the greater occipital nerve, and pierces the tendon of the trapezius muscle. [PICTURE #2]

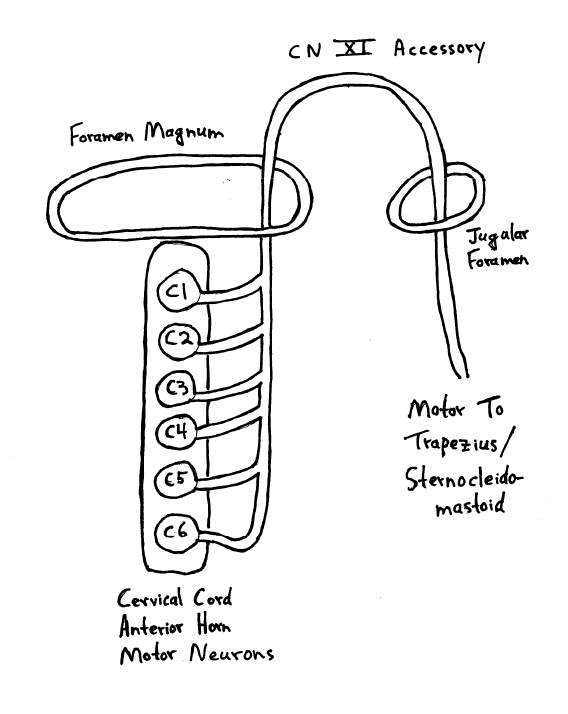

The spinal accessory nerve takes its origin from the entire length of the cervical cord, always as low as the fifth and often as low as the seventh cervical level (see drawing below). Any acute flexion, extension or torsion of the neck will exert traction on the delicate filaments of the spinal accessory nerve, resulting in spasm of the trapezius and sternocleidomastoid muscles. When the trapezius and suboccipital muscles (especially the inferior oblique muscle) are in spasm, traction is produced upon the greater occipital nerve as it pierces the fascial attachment of these muscles.

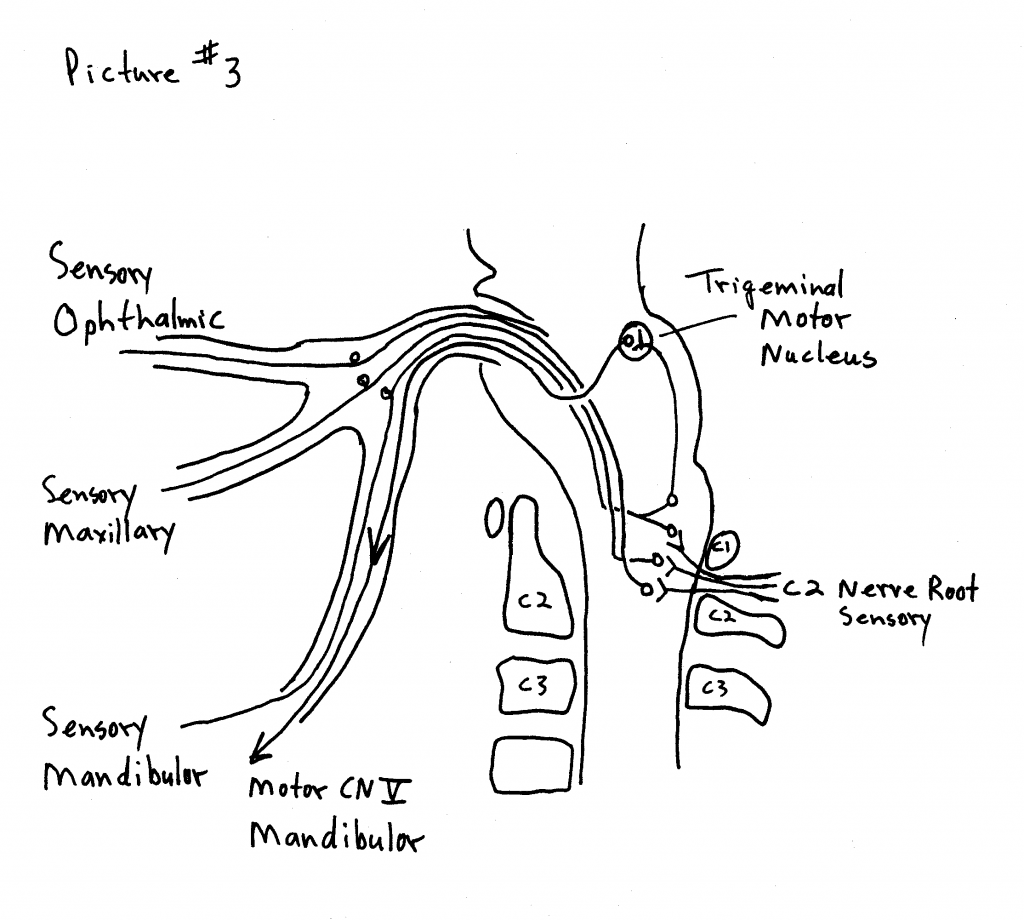

Sensory changes extending over the trigeminal innervation area following whiplash injury to the neck are explained by the communication between the 2nd and 3rd cervical nerve roots and the greater occipital nerve with the trigeminal nerve in the spinal fifth tract in the medulla (trigeminal cervical nucleus). [PICTURE #3] This has been called the greater occipital/trigeminus syndrome, and is a cause of post-whiplash headache. As the ophthalmic fibers descend the deepest into the cervical spine, the headaches are often in the distribution of the ophthalmic branch of cranial nerve V (around and behind the eye).

Following his 1957 publicaton on the subject of craniocerebral injury he was back in 1958 with yet another contribution, this time discussing the cervical spine and its involvement in injuries, Dr. Seletz publishes an article in the Journal of the American Medical Association, titled (2):

Whiplash Injuries

Neurophysiological Basis for Pain and

Methods Used for Rehabilitation

Once again, Dr. Seletz states that whiplash trauma results in “direct trauma to the spinal accessory nerve and to the roots of the cervical nerves.” He states:

“A major portion of the headaches associated with this syndrome are derived from a traction injury to the second cervical nerve root.”

The second cervical nerve root is particularly vulnerable to injury because it is not protected by pedicles and facets, as are the other cervical nerve roots. Additionally, the second cervical nerve root exits between the atlas and axis, “the point of greatest rotation of the head on the neck.” The second nerve root becomes the greater occipital nerve, which innervates the majority of the scalp, the side of the upper neck, and portions of the face.

“The physiological communication between the second cervical and the trigeminal nerves in the spinal fifth tract of the medulla [trigeminal-cervical nucleus] involves the first division of the trigeminal nerve [opthalamic] and thereby gives attacks of hemicrania with pain radiating behind the corresponding eye. This is the mechanism whereby a great many chronic and persistent headaches have their true origin in injury to the second cervical nerve,” noting:

“‘Many headaches are not headaches at all, but really a pain in the neck.’”

Since the greater occipital nerve pierces the tendinous attachment of the trapezius muscle at the base of the skull, trapezius spasm aggravates greater occipital nerve (C2) sensory disturbance. The trapezius is innervated by the spinal accessory nerve, cranial nerve XI. The spinal accessory nerve originates from filaments of the entire length of the cervical spinal cord, ascends through the foramen magnum and leaves the skull through the jugular foramen for a long descent to the trapezius muscle. Persistent spasm of the trapezius muscle is not due to primary injury to the muscles but to traction injury to the delicate filaments of origin of the spinal accessory nerve.

Although Dr. Seletz expertly described the neuroanatomical basis for headaches arising from the cervical spine in the late 1950’s, it took nearly a quarter of a century for officials to include the category “Cervicogenic Headache” in their classification schemes (3). Additions to Dr. Seletz’s concepts on cervicogenic headache continue through today. A recent (August 2008) PubMed search of the National Library of Medicine database using the key words “cervicogenic headache” listed 588 articles, with publication dates ranging from 1949 to 2008.

Perhaps the most detailed anatomical description for the physiological basis for cervicogenic headache was written by Australian physician and researcher Nikoli Bogduk, MD, PhD, in 1995. Dr Bogduk published an article in the journal Biomedicine and Pharmacotherapy titled (4):

Anatomy and Physiology of Headache

In this article, Dr. Bogduk notes that all headaches have a common anatomy and physiology in that they are all mediated by the trigeminocervical nucleus, and are initiated by noxious stimulation of the endings of the nerves that synapse on this nucleus or by irritation of the nerves themselves. The trigeminocervical nucleus is a region of grey matter in the brainstem.

The trigeminocervical nucleus is “defined by its afferent fibers,” and it receives afferents from the following sources:

1) Trigeminal Nerve (Cranial Nerve V)

2) Upper three cervical nerves

3) Cranial Nerve VII (Facial Nerve)

4) Cranial Nerve IX (Glossopharyngeal Nerve)

5) Cranial Nerve X (Vagus Nerve)

All of these sources of afferents terminate on common second-order neurons in the trigeminocervical nucleus, which can then relay the sensations of pain to the cortical brain. The trigeminocervical nucleus is the sole nociceptive nucleus of the head, throat and upper neck. “All nociceptive afferents from the trigeminal, facial, glossopharyngeal and vagus nerves and C1-C3 spinal nerves ramify in this single column of grey matter.” Stimulation of cervical afferents to a second-order neuron that also receives trigeminal afferents may result in the source of stimulation being interpreted as arising in the trigeminal receptive field, resulting in the perception of headache. Pain in the forehead can arise as a result of stimulation by cervical afferents of second-order neurons in the trigeminocervical nucleus that happen also to receive forehead trigeminal nerve afferents.

Dr. Bogduk indicates that because the ophthalmic branch of the trigeminal nerve extends the farthest into the trigeminocervical nucleus, cervical afferent stimulation is most likely to refer pain to the frontal-orbital region of the head. Yet, importantly, any structure innervated by any of the three branches (ophthalmic, maxillary, mandibular) of cranial nerve V (trigeminal) can be painful as a consequence of irritation of any of the structures innervated by the C1, C2, and/or C3 nerve roots. The following lists are helpful:

Structures innervated by ophthalmic branch (V1) cranial V (trigeminal):

Skin of forehead

Orbit

Eye

Frontal sinus

Dura mater of the anterior cranial fossa

Anterior and posterior ends of the falx cerebri

Superior sagittal sinus

Proximal ends of the anterior and middle cerebral arteries

Superior surface of the tentorium cerebelli

Cavernous sinus

Venous sinuses

Temporal artery

Structures innervated by maxillary branch (V2) cranial V (trigeminal):

Nose

Paranasal sinuses

Upper teeth

Upper jaw

Dura mater of the middle cranial fossa

Structures innervated by mandibular branch (V3) cranial V (trigeminal):

Dura mater of the middle cranial fossa

Lower teeth

Lower jaw

Temporomandibular joint

External auditory meatus (ear)

Anterior aspect of the tympanic membrane

Structures innervated by C1-C3:

Dura mater of the posterior cranial fossa

Inferior surface of the tentorium cerebelli

Anterior and posterior upper cervical and cervical-occiput muscles

OCCIPUT-C1, C1-C2, and C2-C3 joints

C2-C3 intervertebral disc

Skin of the occiput

Vertebral arteries

Carotid arteries

Alar ligaments

Transverse ligaments

Trapezius muscle

Sternocleidomastoid muscle

Dr. Bogduk agrees with the writings from Dr. Seletz decades before in that the C1 and C2 nerve roots are particularly likely to be involved in the genesis of cervicogenic headache because the C1 and C2 spinal nerve roots “do not emerge through intervertebral foramina.” This make these nerve roots more vulnerable to stretch or compressive stresses. Additionally, Dr. Bogduk also agrees with Dr. Seletz in noting that the sensory component of the C2 posterior primary rami becomes the greater occipital nerve. C2 winds under the inferior oblique muscle, ascends and pierces the shared aponeurosis of the trapezius and sternocleidomastoid muscle to supply the posterior scalp.

Two other clinically relevant points

Dr. Bogduk makes in this article include:

1) Arthritic changes of the upper cervical synovial joints (including C2-C3) can cause neck pain and headache.

2) C2 neuralgia can cause headache as a consequence of “scar tissue following trauma to the lateral atlanto-axial joint.”

In 2005, adding to the more recent data on this topic, Dr. David Biondi, an instructor in Neurology Harvard Medical School, published an article titled (5):

Cervicogenic Headache:

A Review of Diagnostic and Treatment Strategies

In this article, Dr. Biondi makes the following key points:

- “Cervicogenic headache is a relatively common cause of chronic headache that is often misdiagnosed or unrecognized.”

- Cervicogenic headache is chronic hemicranial pain that is referred to the head from tissues of the neck.

- Head pain that is referred from the tissues of the neck is called cervicogenic headache.

- Cervicogenic headache was not officially recognized until 1983.

- The key neurological structure in cervicogenic headache is the trigeminocervical The trigeminocervical nucleus is a region in the upper cervical spinal cord where sensory nerve fibers from the trigeminal nerve (cranial V) interact with sensory fibers from the upper cervical nerve roots.

- The convergence of upper cervical and trigeminal sensory fibers is the basis for upper cervical problems causing pain in the face and head.

- Cervicogenic headache is often a sequelae of head or neck injury but may occur in the absence of trauma.

- The prevalence of cervicogenic headache is as high as 20% of patients with chronic

- Cervicogenic headache is four times more prevalent in women.

- “Patients with cervicogenic headache will often have altered neck posture or restricted cervical range of motion.”

- Cervicogenic headache pain can be “triggered or reproduced by active neck movement, passive neck positioning especially in extension or extension with rotation toward the side of pain, or on applying digital pressure to the involved facet regions or over the ipsilateral greater occipital nerve.”

- Zygapophyseal joint, cervical nerve, or medial branch blockade is used to confirm the diagnosis of cervicogenic headache.

- Trauma to or pathologic changes to the C1-C2-C3 joints can cause head pain.

- The third occipital nerve (dorsal ramus C3) innervates the C2–C3 facet joint; the C2- C3 facet joint and the third occipital nerve are the most vulnerable to trauma from acceleration-deceleration whiplash injuries of the neck. Therefore, injury to the C2-C3 facet joint is the most common cause of post-traumatic cervicogenic

- It can take a year or longer for post-whiplash cervicogenic headache to resolve.

- Disc problems as low as C5–C6 can cause chronic cervicogenic headache.

- The following structures can cause cervicogenic headache:

- The greater occipital nerve (dorsal ramus C2)

- The lesser occipital nerve

- The atlanto-occipital joint

- The atlantoaxial joint

- The C2 or C3 spinal nerve

- The third occipital nerve (dorsal ramus C3)

- The zygapophyseal joint(s) as low as C5

- The intervertebral discs as low as C5-C6

In addition to these points, Dr. Biondi notes that in the management of cervicogenic headache, drugs alone are often ineffective. He states that “Many patients with cervicogenic headache overuse or become dependent on analgesics.” He also notes that COX-2 inhibitors cause both gastrointestinal and renal toxicity after long-term use, and they cause an increased risk of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events.

Dr. Biondi is an osteopathic physician, and therefore has an understanding of manual and manipulative techniques. He states:

“All patients with cervicogenic headache could benefit from manual modes of therapy and physical conditioning.”

Dr. Biondi notes that the treatment of cervicogenic headache usually requires manipulation of the upper cervical facet joints, and that manipulative techniques are particularly well suited for the management of cervicogenic headache, including high velocity, low amplitude manipulation. These techniques are commonly used by chiropractors in the management of cervicogenic headaches.

In October of 1997, a randomized, blinded study on the treatment of cervicogenic headache that included chiropractic adjustments to the cervical spine was published (6). The study participants had cervicogenic headaches in accordance with the standards of the International Headache Society. The group receiving chiropractic cervical spine adjustments obtained statistically significant improvements in all three measurement criteria. Specifically, subjects receiving chiropractic adjustments for their cervicogenic headache:

- Decreased their analgesic use by 36%.

- Decreased their headache hours by 69%.

- Decreased their headache intensity by 36%.

Using gold standard research protocols, this study reveals that chiropractic spinal adjusting can benefit a large number of patients suffering from cervicogenic headache.

Diagnostic Criteria for Cervicogenic Headache

(Developed by the Cervicogenic Headache International Study Group)

THE PATIENT MUST HAVE AT LEAST ONE OF THE FOLLOWING:

- The head pain must be preceded by:

Neck Movementor

Sustained Awkward Head Positioning

or

External Pressure Over the Upper Cervical (C1-2-3-4) or

Occipital Region on the Symptomatic Side - Restricted Cervical Spine Range of Motion (Active and Passive)

Ipsilateral Neck, Shoulder, or Arm Pain of a Vague Nonradicular Nature

or

Occasional Arm Pain of a Radicular nature

If All Three Criteria Are Present, One Is Essentially Assured of Cervicogenic Headache

CHARACTERISTICS OF CERVICOGENIC HEADACHE

Frequently a History of Indirect Neck Trauma [Whiplash injury]

Unilateral Headache That Does Not Change Sides

Occasionally the Pain May Be Bilateral

The Pain is Located Occipitally, Frontally, Temporally, or Orbitally

The Pain Can Last Hours to Days

The Headache Usually Begins in the Neck

The Headache is Moderate to Severe

The Headache is Non-Throbbing

The Headache is Non-Lancinating

THE FOLLOWING FEATURES

MAY ALSO BE OCCASIONALLY NOTED

Nausea

Phonophobia

Photophobia

Dizziness

Difficult Swallowing

Ipsilateral Blurred Vision

Vomiting

Ipsilateral Lacrimation

Ipsilateral Edema, Especially in the Periocular Region

REFERENCES

- Seletz E; Craniocerebral Injuries and the Postconcussion Syndrome; Journal of the International College of Surgeons; January, 1957; 27(1):46-53.

- Seletz E; Whiplash Injuries, Neurophysiological Basis for Pain and Methods Used for Rehabilitation; Journal of the American Medical Association; November 29, 1958, pp. 1750 – 1755.

- Sjaastad O; “Cervicogenic Headache” An Hypothesis; Cephalagia; December 1983; 3(4):249-256.

- Bogduk N; Anatomy and Physiology of Headache; Biomedicine and Pharmacotherapy; 1995, Vol. 49, No. 10, 435-445.

- Biondi DM; Cervicogenic Headache: A Review of Diagnostic and Treatment Strategies; Journal of the American Osteopathic Association; April 2005, Vol. 105, No. 4 supplement, pp. 16-22.

- Nilsson N; The effect of spinal manipulation in the treatment of cervicogenic headache; Journal of Manipulative and Physiological Therapeutics; June 1997; 20(5):326-330.