How Safe Are Chiropractic Adjustments?

In recent years the safety and efficacy of Chiropractic adjustments / manipulation have come into question. And simultaneously the accusations against spinal manipulation / Chiropractic adjustments have come under equal fire. It is the hope of this months issue to alleviate the questions surrounding this clinical approach and it’s utilization

In 1985, the late physician W. H. Kirkaldy-Willis (d. 2006 at age 92) was the lead author in an article published in the journal Canadian Family Physician (1), titled:

“Spinal Manipulation in the Treatment of Low back Pain”

Dr. Kirkaldy-Willis was a Professor Emeritus of Orthopedics and director of the Low-Back Pain Clinic at the University Hospital, Saskatoon, Canada. In this article, Dr. Kirkaldy-Willis notes:

“Spinal manipulation, one of the oldest forms of therapy for back pain, has mostly been practiced outside of the medical profession.”

“Over the past decade, there has been an escalation of clinical and basic science research on manipulative therapy, which has shown that there is a scientific basis for the treatment of back pain by manipulation.”

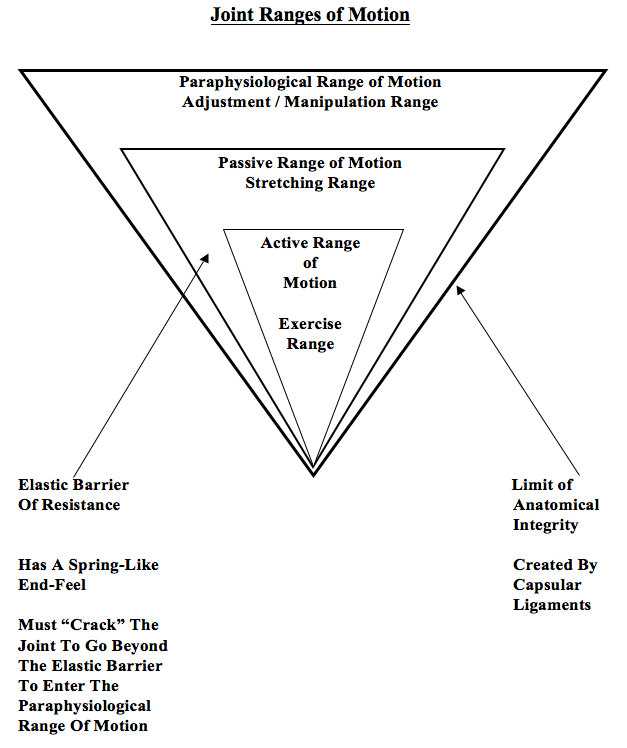

In his explanation of the biomechanics of spinal manipulation, Dr. Kirkaldy-Willis uses the following graphic:

The graphic shows that joint motion is divided into three distinct categories:

1) Active Range of Motion

This is the range of motion the patient can achieve through their own active efforts.

2) Passive Range of Motion

This range of motion is primarily achieved by the physician / therapist who pushes the involved joint beyond the active range of motion. The passive range of motion is greater than the active range of motion. The passive range of motion will influence a larger range of tissue than does the active range of motion.

Dr. Kirkaldy-Willis states (1):

“Beyond the end of the active range of motion of any synovial joint, there is a small buffer zone of passive mobility.” A joint can only move into this zone with passive assistance, and going into this passive range of motion “constitutes mobilization.”

[This is mobilization, not manipulation]

3) Paraphysiological Range of Motion

This range of motion is only achieved by moving beyond the Passive Range of Motion.

Dr. Kirkaldy-Willis states (1):

“At the end of the passive range of motion, an elastic barrier of resistance is encountered. This barrier has a spring-like end-feel.”

“If the separation of the articular surfaces is forced beyond this elastic barrier, the joint surfaces suddenly move apart with a cracking noise.”

“This additional separation can only be achieved after cracking the joint and has been labeled the paraphysiological range of motion.”

“This constitutes manipulation.” [Important]

“The cracking sound on entering the paraphysiological range of motion is the result of sudden liberation of synovial gases—a phenomenon known to physicists as cavitation.”

Following cavitation, a synovial bubble can be observed on x-rays, which is reabsorbed over the following 30 minutes. During this “refractory period” there is no resistance between the passive and paraphysiological zones.

Concerning spinal manipulation, Dr. Kirkaldy-Willis also makes the following

Points (1):

“At the end of the paraphysiological range of motion, the limit of anatomical integrity is encountered. Movement beyond this limit results in damage to the capsular ligaments.”

Joint manipulation [adjusting] “requires precise positioning of the joint at the end of the passive range of motion and the proper degree of force to overcome joint coaptation” [to overcome the resistance of the joint surfaces in contact].

“With experience, the manipulator can be very specific in selecting the spinal level to be manipulated.”

“Most family practitioners have neither the time nor inclination to master the art of manipulation and will wish to refer their patients to a skilled practitioner of this therapy.”

“The physician who makes use of this resource [manipulation] will provide relief for many back pain patients.”

Dr. Kirkaldy-Willis suggests... (1) that during spinal manipulation, there is a stretching of facet joint capsules which fires the capsular mechanoreceptors. This will reflexly “inhibit facilitated motoneuron pools” which are responsible for the muscle spasms that commonly accompany low back pain. The result of this inhibition is an improvement of joint movement. The improved movement initiates the Gate Theory of Pain, originally published in 1965 by Ronald Melzack and Patrick Wall in the journal Science (2).

This theory has “withstood rigorous scientific scrutiny.” “The central transmission of pain can be blocked by increased proprioceptive input.” Pain is facilitated by “lack of proprioceptive input.” This is why it is important for “early mobilization to control pain after musculoskeletal injury.”

The facet capsules are densely populated with mechanoreceptors. “Increased proprioceptive input in the form of spinal mobility tends to decrease the central transmission of pain from adjacent spinal structures by closing the gate. Any therapy which induces motion into articular structures will help inhibit pain transmission by this means.”

Furthermore, in chronic cases, there is a shortening of periarticular connective tissues and intra-articular adhesions may form; manipulations [chiropractic adjustments] can stretch or break these adhesions. Consequently, “In most cases of chronic low back pain, there is an initial increase in symptoms after the first few manipulations [probably as a result of breaking adhesions]. In almost all cases, however, this increase in pain is temporary and can be easily controlled by local application of ice.”

The main point stressed by Dr. Kirkaldy-Willis is that chronic spinal pain is

often associated with reduced motion, which opens the pain gate. Spinal manipulation is an excellent method to restore the range of motion, close the pain gate, and reduce pain. However, appropriate spinal manipulation is a skill that requires special training and initial supervised applications. When the practitioner is appropriately trained, spinal manipulation is both safe and effective.

Manipulation & The Source Of It’s Checkered Past

In an important and revealing article published in 1995 (3), Alan Terrett reviewed the published literature pertaining to the incidence of reported adverse events associated with chiropractic spinal adjusting (manipulation). Astonishingly, his results revealed that in many of the published adverse events ascribed to chiropractic manipulation were, in fact, not associated with chiropractic in any manner. Apparently, the authors of the articles assumed “chiropractic” and “manipulation” were synonyms. When untrained laypersons or physicians performed a manipulation resulting in a reported adverse event, authors would claim that the manipulation was performed by a chiropractor. The list of discovered manipulators included:

A Blind Masseur

An Indian Barber

A Wife

A Kung-Fu Practitioner

Self Manipulation

Often the manipulation was performed by a medical doctor, an osteopath, a naturopath, or a physical therapist.

Dr. Terrett concluded:

“This study reveals that the words chiropractic and chiropractor commonly appear in the literature to describe spinal manipulative therapy, or practitioner of spinal manipulative therapy, in association with iatrogenic complications, regardless of the presence or absence of professional training of the practitioner involved.”

“The words chiropractic and chiropractor have been incorrectly used in numerous publications dealing with spinal manipulative therapy injury by medical authors, respected medical journals and medical organizations.”

“In many cases, this is not accidental; the authors had access to original reports that identified the practitioner involved as a non-chiropractor. The true incidence of such reporting cannot be determined.”

“Such reporting adversely affects the reader's opinion of chiropractic and chiropractors.”

“It has been clearly demonstrated that the literature of medical organizations, medical authors and respected, peer-reviewed, indexed journals have, on numerous occasions, misrepresented the facts regarding the identity of a practitioner of manual therapy associated with patient injury.”

“Such biased reporting must influence the perception of chiropractic held by the reader, especially when cases of death, tetraplegia and neurological deficit are incorrectly reported as having been caused by chiropractic.”

“Because of the unwarranted negative opinion generated in medical readers and the lay public alike, erroneous reporting is likely to result in hesitancy to refer to and underutilization of a mode of health care delivery.”

In 1996, Woodward and colleagues (4) from the University Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Bristol, UK, published a retrospective study to determine the effects of chiropractic in a group of 28 patients who had been referred with chronic ‘whiplash’ syndrome. The 28 patients in this study had initially been treated with anti-inflammatories, soft collars and physiotherapy. These patients had all become chronic, and were referred for chiropractic care at an average of 15.5 months (range was 3 – 44 months) after their initial injury. Following chiropractic care, 93% of the patients had improved. The title of the article was Chiropractic treatment of chronic ‘whiplash’ injuries, and it was published it the prestigious journal Injury.

Woodward and colleagues defined spinal manipulation as:

“Spinal manipulation is a high-velocity low-amplitude thrust to a specific vertebral segment aimed at increasing the range of movement in the individual facet joint, breaking down adhesions and stimulating production of synovial fluid.”

Woodward and colleagues also note that complications from cervical manipulations are rare, and when they are reported in the literature, they often…

“arose as a result of spinal manipulation performed by non-chiropractors, who had been misrepresented in the literature as being trained chiropractors.” [Important]

With respects to risk associated with cervical manipulation, there is particular concern pertaining to vertebral artery dissection. All chiropractors are well aware of the issue. Vertebral artery dissection is extensively discussed in both chiropractic undergraduate and post graduate continuing educational programs. Entire books are written on the subject and are a part of core curriculum at chiropractic colleges (5). Chiropractors are well schooled on the pertinent anatomy, signs/symptoms, clinical presentations, examination findings, and procedures that may possibly be associated with increased risk.

In 2002, the Journal of Neurology (6) published a study titled:

“Hyperhomocysteinemia: A potential risk factor for cervical artery dissection following chiropractic manipulation of the cervical spine”

In this study, the authors measured total fasting plasma homocysteine concentration in 4 subjects with manipulation-related cervical artery dissection and compared them to a series of patients with spontaneous dissection of the neck arteries. Both groups were then compared to 36 control subjects. Median plasma homocysteine levels were significantly higher in patients with manipulation-related cervical artery dissection (18.2 µmol/l, range 14.3 to 30.0) compared with controls (8.9 µmol/l, range 5 to 17.3). These authors concluded that hyperhomocysteinemia may represent a potential risk factor for manipulation-related cervical artery dissection, leading to structural abnormalities of the arterial wall and increasing the susceptibility to mechanical stress.

Importantly for chiropractors, the authors note that the risk factors used by chiropractors to screen patients at risk for cervical artery dissection from manipulation are usually unrevealing. Therefore, “the population at risk cannot be identified a priori” using standard risk factor screening.

In 2002, Dr. Scott Haldeman from the Department of Neurology, University of California, Irvine, and colleagues, published a study titled (7):

“Unpredictability of cerebrovascular ischemia associated with

cervical spine manipulation therapy: a review of

sixty-four cases after cervical spine manipulation”

The study, published in Spine, was a retrospective review of 64 medicolegal records describing cerebrovascular ischemia after cervical spine manipulation.

The authors note, that in 2002, only about “117 cases of post-manipulation cerebrovascular ischemia have been reported in the English language literature.”

The authors further indicate that proposed risk factors for cerebrovascular ischemia secondary to spinal manipulation include age, gender, migraine headaches, hypertension, diabetes, birth control pills, cervical spondylosis, and smoking, and that it is often assumed that these complications may be avoided by clinically screening patients and by pre-manipulation positioning of the head and neck to evaluate the patency of the vertebral arteries.

After an extensive review, these authors conclude:

“This study was unable to identify factors from the clinical history and physical examination of the patient that would assist a physician attempting to isolate the patient at risk of cerebral ischemia after cervical manipulation.”

“Cerebrovascular accidents after manipulation appear to be unpredictable and should be considered an inherent, idiosyncratic, and rare complication of this treatment approach.”

Earlier this year (2008), Dr. David Cassidy and colleagues published the most comprehensive study to date pertaining to the risk of vertebral artery dissection as related to chiropractic cervical spine manipulation (8). The article was published in Spine, and titled:

“Risk of Vertebrobasilar Stroke and Chiropractic Care:

Results of a Population-Based Case-Control and Case-Crossover Study”

Key points from this article include:

- “Vertebrobasilar artery stroke is a rare event in the population.”

- “We found no evidence of excess risk of vertebral artery stroke associated chiropractic care.”

- “Neck pain and headache are common symptoms of vertebral artery dissection, which commonly precedes vertebral artery stroke.”

- “The increased risks of vertebral artery stroke associated with chiropractic and primary care physicians visits is likely due to patients with headache and neck pain from vertebral artery dissection seeking care before their stroke.”

- Most cases of vertebral arterial dissection occur spontaneously.

- “Because patients with vertebrobasilar artery dissection commonly present with headache and neck pain, it is possible that patients seek chiropractic care for these symptoms and that the subsequent vertebral artery stroke occurs spontaneously, implying that the association between chiropractic care and vertebral artery stroke is not causal.”

- “Since it is unlikely that primary care physicians cause stroke while caring for these patients, we can assume that the observed association between recent primary care physician care and vertebral artery stroke represents the background risk associated with patients seeking care for dissection-related symptoms leading to vertebral artery stroke. Because the association between chiropractic visits and vertebral artery stroke is not greater than the association between primary care physicians visits and vertebral artery stroke, there is no excess risk of vertebral artery stroke from chiropractic care.”

- Neck manipulation “is unlikely to be a major cause” of these rare vertebral artery stroke events.

- “Our results suggest that the association between chiropractic care and vertebral artery stroke found in previous studies is likely explained by presenting symptoms attributable to vertebral artery dissection.”

- “There is no acceptable screening procedure to identify patients with neck pain at risk of vertebral artery stroke.”

In 2004, the American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons published a monograph titled Neck Pain (9). The second to last chapter in the monograph, chapter 7, is titled:

“Manual Therapy Including Manipulation For

Acute and Chronic Neck Pain”

The editor of the monograph is Jeffery Fischgrund, MD, from the Department of Orthopaedic Surgery at William Beaumont Hospital in Royal Oaks, Michigan. This monograph has twelve respected contributors, including the authors of chapter 7, Scott Haldeman, Clinical Professor of Neurology at the University of California, Irvine, and Eric Hurwitz, Associate Professor of Epidemiology at the University of California, Los Angeles. With respect to the safety of spinal manipulation, the authors make the following comments:

“Major complications from manual therapies are extremely rare but, nonetheless, have been a source of much discussion.”

“Estimates of vertebral artery dissections or stroke rates associated with cervical manipulation have ranged form 1 per 400,000 to 1 per 10 million manipulations.”

“An estimate of 1 per 5.85 million manipulations, based on 1988 to 1997 medical record and chiropractic malpractice data from Canada, reflects the experience of practitioners of manipulation.”

“No serious complications from spinal manipulation or other chiropractic forms of manual treatment have been reported from any of the published clinical trials involving manipulation or mobilization for neck pain.”

“It should be noted that complications rates from medications, surgery, and most other neck pain treatments for which data are available are estimated to be higher than those from manual and manipulative therapies.”

The largest prospective study to date assessing the safety of chiropractic spinal manipulation to the cervical spine was published in Spine, October 2007, and titled:

“Safety of Chiropractic Manipulation of the Cervical Spine

A Prospective National Survey”

This study assessed the risk of serious and relatively minor adverse events following chiropractic manipulation of the cervical spine by a sample of U.K. chiropractors. The authors studied treatment outcomes from 19,722 patients from 377 chiropractors that involved 50,276 cervical spine manipulations. Manipulation was defined as the application of a high-velocity/low-amplitude or mechanically assisted thrust to the cervical spine. A serious adverse event was defined as referral to hospital and/or severe onset/worsening of symptoms immediately after treatment and/or resulted in persistent or significant disability/incapacity. Minor adverse events were reported by patients as a worsening of presenting symptoms or onset of new symptoms, were recorded immediately, and up to 7 days, after treatment.

The authors concluded:

“Safety of treatment interventions is best established with prospective surveys, and this study is unique in that it is the only prospective survey on such a large scale specifically estimating serious adverse events following cervical spine manipulation.”

“There were no reports of serious adverse events.”

“Although minor side effects following cervical spine manipulation were relatively common, the risk of a serious adverse event, immediately or up to 7 days after treatment, was low to very low.”

“No significant adverse event was reported by the chiropractors using the definition criteria.”

“The risk rates described in this study compare favorably to those linked to drugs routinely prescribed for musculoskeletal conditions in general practice.”

“The risks reported here are also lower than those reported for acupuncture, which were described as a very safe intervention in the hands of a competent practitioner.”

“Although minor side effects were found to be relatively common, the risk of a serious adverse event, immediately and up to 7 days after treatment, was estimated to be low to very low in these consultations.”

“On this basis, this survey provides evidence that cervical spine manipulation is a relatively safe procedure when administered by registered U.K. chiropractors.”

No therapeutic intervention is without risk. Spinal manipulation has the potential to exceed the limit of anatomic integrity and thus cause injury. The study by Terrett (3) shows that when spinal manipulation is attempted by untrained individuals, there is an increased incidence of adverse events. Chiropractors are well schooled in the potential for injury with certain manipulative maneuvers, and extremely well trained in the effective delivery of safe spinal manipulations. The best-published studies indicate that chiropractic spinal manipulation is both safe and effective.

References

- Kirkaldy-Willis WH and Cassidy JD; Spinal Manipulation in the Treatment of Low back Pain; Canadian Family Physician; March 1985, Vol. 31, pp. 535-540.

- Melzack R and Wall PD; Pain Mechanisms: a new theory; Science; 1965, 150, pp. 971-9.

- Terrett AG; Misuse of the literature by medical authors in discussing spinal manipulative therapy injury; Journal of Manipulative and Physiological Therapeutics; 1995 May;18(4):203-10.

- N. Woodward, J. C. H. Cook, M. F. Gargan and G. C. Bannister; Chiropractic treatment of chronic ‘whiplash’ injuries; Injury; Volume 27, Issue 9, November 1996, pages 643-645.

- Terrett AGJ; Current Concepts in Vertebrobasilar Complications Following Spinal Manipulation; Second Edition, NCMIC Group, 2001.

- Pezzini A, Del Zotto E, Padovani A; Hyperhomocysteinemia: A potential risk factor for cervical artery dissection following chiropractic manipulation of the cervical spine; Journal of Neurology, October 2002, Vol. 249, Issue 10, pp. 1401-1403.

- Haldeman S, Kohlbeck FJ, McGregor M; Unpredictability of cerebrovascular ischemia associated with cervical spine manipulation therapy: a review of sixty-four cases after cervical spine manipulation; Spine; 2002 Jan 1;27(1):49-55.

- Cassidy, J David DC, PhD; Boyle, Eleanor PhD; Côté, Pierre DC, PhD; He, Yaohua MD, PhD; Hogg-Johnson, Sheilah PhD; Silver, Frank L. MD; Bondy, Susan J. PhD; Risk of Vertebrobasilar Stroke and Chiropractic Care: Results of a Population-Based Case-Control and Case-Crossover Study; Spine; Volume 33(4S), February 15, 2008 pp S176-S183.

- Fischgrund, JS; Neck Pain, 2004.

- Thiel, Haymo W. DC, PhD; Bolton, Jennifer E. PhD; Docherty, Sharon PhD; Portlock, Jane C. PhD; Safety of Chiropractic Manipulation of the Cervical Spine, A Prospective National Survey; Spine; Volume 32(21), October 2007, pp 2375-2378.