In 1921, physician Henry Winsor, MD, from the University of Pennsylvania, performed meticulous necropsies on 50 cadavers, and published the results in the journal Medical Times. A unique interest of Dr. Winsor was the stages of spinal dysfunction and spinal degenerative disease.

Dr. Winsor discovered that 49 of the 50 cadavers displayed minor curvatures of the spine, and that these regions of spinal curvature shared another characteristic: they were quite fixed, rigid. He noted that at the area of the involved regions, “there was intense rigidity of the segments.” His exact description was:

“All curves and deformities of the spine were rigid, apparently of long duration; irreducible by ordinary manual force: extension, counter-extension, rotation, even strong lateral movements failed to remove them or even cause them to change their relative positions.”

Based upon his observation of cadavers at varying stages of life, Dr. Winsor noted that spondylosis is a process, with the last stage being fixation of segments. He described the spondylosis process, using the example of a short leg resulting in pelvic obliquity, sacroiliac joint adaptation, and spinal compensation. His exact description was:

A “sacro-iliac subluxation, an apparent shortening of the leg, comparative elevation of the posterior superior iliac spine of the ilium, combined with lateral curve in the lumbar region, lumbar curve and sacro-iliac subluxation (rotation of the innominate) appear to be interdependent.”

Subsequent to this series of malpositions, Dr. Winsor describes the sequence of the spondylotic process in three stages of histological change, as follows:

1) Minor spinal curves develop, such as the so-called sacroiliac subluxations.

2) The regions of spinal curvature become stiffer. The muscles are converted into ligaments, and the ligaments are converted to bone.

3) Ultimately true spinal segmental bony ankylosis occurs.

Dr. Winsor concludes that this progressive stiffening of the spinal segments is not desirable. He terms this spinal stiffening as a “disease,” and implies that avoidance of this stiffening is preferred. His statements include:

“The disease appears to precede old age and to cause it. The spine becomes stiff first and old age follows. Therefore, we may say a man is as old as his spine.”

The Human Spine in Health & Disease

In their authoritative book, The Human Spine in Health and Disease, George Schmorl and Herbert Junghanns describe the pathology of the “Inefficient Motor Segment” or “Intervertebral Insufficiency.”

George Schmorl (1861-1932) was a German physician and pathologist. Herbert Junghanns (1902-1986) was the Chief of the Occupational Accident Hospital, Surgical Clinic, and Head of the Institute for Spinal Column Research, in Frankfurt, Germany. The first edition of their book was published in 1932, shortly before the death of Dr. Schmorl. The fifth German edition of their book was translated into English in 1971. Their pioneering reference book contains 500 figures of radiographs, histological sections, photographs, and drawings. The book has more than 500 pages and approximately 5,000 references in the bibliography.

In their discussion pertaining to the “Inefficient Motor Segment” or “Intervertebral Insufficiency,” Schmorl and Junghanns describe a series of events beginning with loosening, resulting in irritation to muscles, joints, and nerves; this is followed, eventually by stiffening and perhaps, occasional joint locking. At first, the loosening is asymptomatic because the associated muscles adequately compensate it for. However, a trivial “additional stimulus” may cause collapse of the compensating mechanism, and the quiescent mechanical problem becomes symptomatic.

Schmorl and Junghanns note:

“For the great majority of patients with complaints of vertebral insufficiency (loosening, fusion, stiffening, immobility, locking), the choice of treatment is conservative.”

“The possibilities of conservative treatment are manifold. Every physician involved with the treatment of spondylogenic symptoms and syndromes should acquire extensive knowledge of the various methods of treatment.”

“Conservative treatment methods have been known since antiquity. They were applied in the presence of symptoms which today are considered part of the concept of intervertebral insufficiency.”

“Previously and into our own time, methods of ‘manual spinal treatment’ have been in the hands of lay therapists. Yet, these methods of treatment have gained access into the medical thinking and treatment and are now known under different names: chiropractice, chirotherapy, osteopathy, forcible manual corrections, manual vertebral therapy, etc.”

“The first goal of treatment can be achieved by strengthening the muscles which are of importance for the spine. This requires loosening chronically tense muscles, strengthening weak muscles and restoring improperly exposed muscles (due to deformities of spinal curvatures, inclined positions, etc.) to the best possible normal function.”

Manual therapy methods “include chiropractice, osteopathy and similar methods which can be termed as manual therapy of the spine. Their beginnings can be traced back into medical history. The proper application and success of these methods within the framework of spinal therapy shows that they are successful in selective cases of spondylogenic disease.” “They often bring sudden relief of nervous pressure or interrupt the improper reflex chain and thereby produce an immediate relief of symptoms.”

Nearly six decades after the publication of the first edition of The Human Spine in Health and Disease, in 1990 Dr. Herbert Junghanns published a book titled Clinical Implications of Normal Biomechanical Stresses on Spinal Function. In the chapter titled “The Intervertebral Motor Unit or Segment,” Dr. Junghanns describes how the intervertebral disc requires the influence of proper segmental motion in order to stay healthy. Specifically, because the intervertebral disc is avascular, nutrients arrive from a motion-dependent pumping mechanism through the cartilaginous end plates of the vertebral bodies above and below an individual disc. Consequently, impaired segmental motion begins the process of disc disease and the first phase of segmental insufficiency. Dr. Junghanns states:

“One external influence is certainly lack of motion, which leads to a slower pump mechanism or even to a complete halt of the pump mechanism. Because of the insufficient interplay in the diffusional flow, nutrients and substances that need to be removed accumulate in the intervertebral disc tissues that are insufficiently supplied. Therefore a lack of or insufficient motion may damage the segmental element with the largest mass, ie, the intervertebral disc.”

The Pathophysiology of Vertebral Segmental Insufficiency

Consistent with his descriptions of the pathophysiology of vertebral segmental insufficiency, Dr. Junghanns suggests the applications of therapy that restores the initial lack of proper motion. Because his described vertebral segmental insufficiency is neuro-mechanically based, his recommendations are as follows:

“The distinct as well as the hidden syndromes of intervertebral insufficiency require a treatment adapted to the state of the illness. Often, manual therapeutic manipulations, physical therapy, and massages will be emphasized.”

These descriptions of vertebral segmental insufficiency, pathophysiological process, and treatment are remarkably similar to those presented by Dr. Vert Mooney when he delivered his Presidential Address of the International Society for the Study of the Lumbar Spine. This speech was delivered at the 13th Annual Meeting of the International Society for the Study of the Lumbar Spine, May 29-June 2, 1986, Dallas, Texas. It was published in the journal Spine in 1987.

Dr. Mooney’s speech pertained to the lumbar spine, and was titled:

Where Is the Pain Coming From?

In his presentation, Dr. Mooney describes the avascular nature of the intervertebral disc, the disc dependence on a pumping motion to ensure proper nutrition and health, and the value of mechanical therapy. Specifically, Dr. Mooney states:

“Anatomically the motion segment of the back is made up of two synovial joints and a unique relatively avascular tissue found nowhere else in the body - the intervertebral disc. Is it possible for the disc to obey different rules of damage than the rest of the connective tissue of the musculoskeletal system?”

“Mechanical events can be translated into chemical events related to pain.”

“Mechanical activity has a great deal to do with the exchange of water and oxygen concentration” in the disc.

An important aspect of disc nutrition and health is the mechanical aspects of the disc related to the fluid mechanics.

The pumping action maintains the nutrition and biomechanical function of the intervertebral disc. Thus, “research substantiates the view that unchanging posture, as a result of constant pressure such as standing, sitting or lying, leads to an interruption of pressure-dependent transfer of liquid. Actually the human intervertebral disc lives because of movement.”

“The fluid content of the disc can be changed by mechanical activity.”

“In summary, what is the answer to the question of where is the pain coming from in the chronic low-back pain patient? I believe its source, ultimately, is in the disc. Basic studies and clinical experience suggest that mechanical therapy is the most rational approach to relief of this painful condition.”

“Prolonged rest and passive physical therapy modalities no longer have a place in the treatment of the chronic problem.”

“Managing Low Back Pain…”

Perhaps the best discussion of the pathophysiological process leading to spinal segmental spondylosis is presented by the late (d. 2006) William H Kirkaldy-Willis, MD. Dr. Kirkaldy-Willis was Emeritus Professor, Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, University Hospital, University of Saskatchewan College of Medicine. In his 1988 (second edition) book Managing Low Back Pain, there are 19 international multidisciplinary distinguished contributing authors. Dr. Kirkaldy-Willis authored a chapter in the book titled:

The Three Phases of the Spectrum of Degenerative Disease

Dr. Kirkaldy-Willis describes how spinal segments are comprised of a three-joint complex: the two posterior facet joints and the intervertebral disc. He notes that the three joints always work together, stating:

“Changes affecting the posterior joints also affect the disc, and visa versa.”

Consequently, injury or stress to any single component of the three-joint complex will mechanically affect the other two components. His breakdown of the three phases of spinal degenerative disease is as follows:

First Phase of Spondylosis

“Dysfunction”

In the first phase, the normal function of the three-joint complex is interrupted as a consequence of injury or chronic stress. This causes the posterior musculature of the involved segment to go into a state of hypertonic contraction. This restricts normal movement. The hypertonic contraction of the muscles also causes muscle ischemia, causing pain. The muscle hypertonicity also causes a slight misalignment of the posterior facet joints, which is known as a “subluxation.” Eventually tissue fibrosis begins to appear.

Second Phase of Spondylosis

“Instability”

If the first phase is allowed to persist, the second phase will eventually ensue. In the second phase, there is abnormal increased movement. Laxity of the posterior joint capsule and of the annulus fibrosus is seen in anatomical sections. Local fibrosis is problematic because “the collagen of scar tissue is not as strong as normal collagen.” Therefore, there is increased propensity for additional injury, inflammation, pain, and muscle hypertonicity.

Third Phase of Spondylosis

“Stabilization”

If the second phase is allowed to persist, the third phase will eventually ensue. In the third phase, degenerative changes begin to appear. As the degenerative changes advance, the unstable segment regains its stability because of fibrosis and osteophytes form around the posterior joints and within and around the disc. In this stabilization phase, the facet joints will progress through the following sequence:

Events Of The Stabilization Phase

Synovitis

![]()

Degeneration of Articular Hyaline Cartilage

![]()

Development of Intra-articular Adhesions

![]()

Increasing Capsular Laxity

![]()

Subluxation of the Joint Surfaces

![]()

Formation of Subperiosteal Osteophytes

![]()

Enlargement of Both Inferior and Superior Facets

![]()

Ultimately Greatly Reduced Movement

Simultaneously with this sequence of changes in the facet joints, there are parallel changes in the intervertebral disc. These changes follow this sequence:

The Development of Small Circumferential Tears in the Annulus Fibrosis

![]()

The Circumferential Tears in the Annulus Become Larger and Coalesce to form Radial Tears that Pass From the Annulus to the Nucleus Pulposus

![]()

Eventual Internal Disruption of the Disc

![]()

Disc Degeneration with Disc Resorption

![]()

Peripheral Osteophytes Around the Circumference of the Disc

![]()

Ultimately Greatly Reduced Movement

Importantly, Dr. Kirkaldy-Willis indicates that during the First Phase or Dysfunction Phase is when most patients experience their first episode of back pain. Even more important, Dr. Kirkaldy-Willis indicates that the pathological changes during the First Phase are minor and potentially reversible. He states:

“During this phase [Dysfunction Phase] the pathological changes are relatively minor and perhaps reversible.”

Only the First Phase, the Phase of Dysfunction, has altered biomechanical properties that are wholly reversible. An important question is?

What treatment is appropriate for these altered biomechanical properties?

Dr. Kirkaldy-Willis and his colleague Dr. J. David Cassidy answer this question with the following paragraph:

“Manipulation is an art that requires much practice to acquire the necessary skill and competence. Few medical practitioners have the time or inclination to master it. This modality has much to offer to the patient with low back pain, especially in the earlier stages during the phase of dysfunction. The majority of patients are first seen while in this phase. Most practitioners of medicine, whether family physicians, or surgeons, will wish to refer their patients to a practitioner of manipulative therapy with whom they can cooperate, whose work they know, and whom they can trust. The physician who makes use of this resource will have many contented patients and save himself many headaches.”

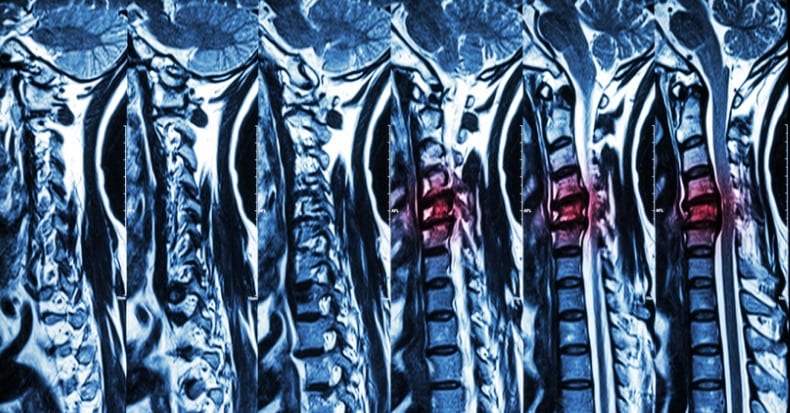

In September of 2008, researchers (Alyas, Connell, Saifuddin) from the Department of Radiology, The Royal National Orthopaedic Hospital NHS Trust, Stanmore, Middlesex, UK, compared recumbent spinal MRI to upright dynamic (motion) spinal MRI. They published their findings in the prestigious journal Clinical Radiology. These authors claim that “dynamic changes in soft-tissue structures” which are related to a patient’s clinical presentation are more appropriately ascertained by upright dynamic MRI than with the more conventional recumbent MRI. They note:

“Upright MRI in the flexed, extended, rotated, standing, and bending positions, allows patients to reproduce the positions that bring about their symptoms and may uncover MRI findings that were not visible with routine supine imaging. Assessment of the degree of spinal stability in the degenerate and postoperative lumbar spine is also possible.”

“Clinical symptoms can develop with sitting, standing, or dynamic maneuvers (including flexion and extension) and may not be adequately assessed by supine MRI.”

“Development of these symptoms reflects the morphological changes in normal or degenerate disco-ligamentous structures due to the effects of gravity, changes in size of the intervertebral foramen, and relative motion between adjacent vertebrae on assumption of the upright posture and with dynamic maneuvers.”

“Therefore, upright and dynamic imaging is important.”

“Imaging in the physiologically representative upright position and with kinetic maneuvers, allows accurate assessment and measurement of changes in the relationship between the components of the functional spinal unit and the potential to correlate radiological signs with positional symptoms.”

“Imaging in the supine position and with non-dynamic methods can only identify indirect radiological signs of instability (i.e., degenerative changes of the disc, ligaments, and facet joints) and some direct signs (malalignment of the vertebral bodies). Upright and positional MRI can demonstrate changes in intersegmental motion that may correlate with clinical symptoms of low back pain and neurogenic claudication.”

In their evaluation of dynamic upright spinal MRI, these authors describe the phases of spinal spondylosis in a similar fashion to Drs. Winsor, Schmorl, and Junghanns. The three phases they describe are:

1) Phase One:

“Initially, there is abnormal motion of the spinal segment (disc, adjacent vertebrae, ligaments, facet joints) and pathological signs of degeneration are minimal; this stage being termed ‘spinal dysfunction’”.

“The signs of relative spinal motion (e.g., translation and sagittal rotation of the vertebral bodies with respect to each other) can be uncovered with upright/positional MRI.”

2) Phase Two or “instability phase.”

“Signs of degeneration are more prominent and there is increased and abnormal intersegmental movement. Instability can be demonstrated as relative hypermobility at the spinal motion segment compared with adjacent motion segments on positional MRI.”

“The disc below a degenerate spinal level can be susceptible to degeneration and can be identified by increased degree of motion.”

3) Phase Three:

“As degeneration progresses, fibrosis and osteophytosis result in re-stabilization and consequential reduction in movement.”

The analysis of spinal segmental spondylosis by Dr. Winsor was based upon his detailed assessment of human cadavers. The analysis of spinal segmental spondylosis by Dr. Kirkaldy-Willis was based upon clinical evaluation, varying forms of imaging, and an assortment of histological collections. The analysis of spinal segmental spondylosis by Dr. Alyas and colleagues was based on dynamic motion MRI performed in the upright weight-bearing position. All three authors found a similar sequence of events that lead to end-stage spinal degenerative disease. Dr. Vert Mooney emphasized the importance of vertebral segmental motion in the health and pain management of the intervertebral disc. Drs. Schmorl, Junghanns, and Kirkalady-Willis discuss the value of manual therapy, mobilizations, exercise, massage and manipulation in the management of especially the earliest phases of spinal segmental dysfunction.

In his 1964 book Joint Pain, Diagnosis and Treatment Using Manipulative Techniques, John McM. Mennell, MD well describes the pathophysiology of pre-arthritic joint pain. Dr. McM. Mennell was Associate Professor, Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine and Attending Physician, Veterans Administration Hospital, Philadelphia. In the preamble of his text, Dr. McM. Mennell makes the following points:

“There can be few physicians who, at one time or another, have not been baffled by the clinical fact that, after a joint has been immobilized for any reason, there is pain and stiffness in it. It is striking that the pain will disappear only after the stiffness has disappeared.”

“Joint dysfunction is a pain producing pathological condition that causes loss of movement, and restoration of normal joint play by manipulation is the logical and the only reasonable treatment to relieve pain from it and to restore normal voluntary movement.”

“The recognition of joint dysfunction can only be achieved by clinical means.”

“The completion of any movement of joint play can be demonstrated by stress x-rays. Stress x-rays, however, cannot be made routinely.”

…Reduction Of Segmental Vertebral Motion Is Not Correctable By Performing Voluntary Exercises.

The summary of the references cited above indicates that spinal segmental spondylosis is a process that begins with an irritation or stress that results in hypertonic segmental muscles and a consequent reduction in motion. This reduction of segmental vertebral motion is not correctable by performing voluntary exercises.

Following this initial reduction of segmental vertebral motion, there is a progression of pathophysiology that eventually leads to significant degenerative disease and a marked limitation of spinal motion. Historically, the various stages of spinal degeneration could be proven with stress x-rays, as noted by Dr. McM. Mennell in his 1964 text. Most recently, Dr. Alyas and colleagues have shown that the various stages of spinal degeneration could be proven with dynamic upright weight-bearing MRI. However, it is not reasonable to routinely obtain such diagnostic imaging on most patients.

In contrast, subtle alterations in normal segmental vertebral motions can be ascertained by a chiropractor trained in the ability to assess joint end-play. The authors above also have a consensus that most back pain begins in the earliest phases of segmental joint dysfunction, and that appropriate management at that time can reverse the pathophysiological process. Appropriate management mentioned by these authors includes manual therapy, mobilizations, exercise, massage and manipulation.

This approach to understand the actual pathophysiological process of spinal segmental spondylosis, the training to be able to ascertain subtle segmental motion dysfunctions, and skills necessary to manually abort the process are the educational emphasis of today’s modern chiropractor.

References

Winsor H; Sympathetic Segmental Disturbances: The Evidences of the Association, in Dissected Cadavers, of Visceral Disease with Vertebral Deformities of the Same Sympathetic Segments; Medical Times, November 1921, pp. 1-7.

Junghanns H; Schmorl’s and Junghanns’ The Human Spine in Health and Disease; Grune & Stratton; 1971.

Junghanns H; Clinical Implications of Normal Biomechanical Stresses on Spinal Function; Aspen, 1990.

Mooney V; Where Is the Pain Coming From? Spine, 12(8), 1987, 754-759.

Kirkaldy-Willis H; Managing Low Back Pain, Second Edition, Chruchill Livingstone, 1988.

Alyas F, Connell D, Saifuddin A; Upright Positional MRI of the Lumbar Spine; Clinical Radiology; Volume 63, Issue 9, September 2008, Pages 1035-1048.

McM. Mennell J; Joint Pain, Diagnosis and Treatment Using Manipulative Techniques, Little, Brown, 1964.